By: Andrew DeMil and Michael Borntreger

“Student Perception of online translators: Do they do more harm than good?”

Abstract

Though most second-language instructors are aware that some students use web-based machine translation (WBMT) in order to complete assignments, little is known as to why students decide to utilize such tools and how they may affect the acquisition of their target language (White & Heidrich, 2013). In this study, the researchers surveyed students in advanced Spanish courses at The University of Tampa investigating their perception of WBMT, and how use may have affected their Spanish acquisition. The results report that students have a variety of reasons for which they use these tools, and their beliefs regarding their usefulness also vary.

Background

In White & Heidrich’s 2013 study titled Our Policies, Their Text: German Language Students’ Strategies with and Beliefs about Web-Based Machine Translation, the researchers employed surveys, a translation task, and interviews in order to investigate German language students’ motivations and perceptions regarding the use of WBMT for completing assignments in their undergraduate university-level language classes. They found that students reported to have learned to modify their native English input into the translation tools so as to avoid output errors. Furthermore, in the translation task, many students removed or simplified clauses from the output that they did not comprehend well, which often rendered a grammatically-correct translation but with missing information. The researchers concluded that this suggests that students, even with the help of WBMT, are unable to produce translations far beyond their language level.

In Larson-Guenette, 2013, a similar study to White & Heidrich the researchers used a questionnaire and interviews to gather data related to English speaking students’ motivation and habits regarding the use of WBMT for their German coursework. Results from this study show that students reported to use translation tools and online dictionaries to check and compare their work with the output generated by these services, and that students reported to have a mixed view regarding the efficacy of the use of WBMT regarding their language acquisition. Some students reported that they believed that WBMT has increased their vocabulary but decreased their understanding of the grammar, and some reported that having easy access to computer generated verb tables and other resources that are found on online dictionaries greatly helps their understanding of the language. Others reported that they were not sure how the access to such tools has affected their language acquisition and that they primarily use the services as a means of saving time. The researcher concluded that these mixed results imply that the efficacy of the use of WBMT depends on the way that they are used and the attitudes that accompany this use.

In O’Neill 2012, a study that consisted of 32 intermediate L2 French learners, the researcher solicited compositions from three distinct groups: (1) students who were permitted to use WBMT and had attended a training session regarding their use, (2) students who were permitted to use WBMT but had not attended a training session, and (3) students who were not permitted to use WBMT and thus had not attended a training session (control). Compositions were graded based on various criteria. The results showed that group #2 performed equally to or slightly better than the control group, and group #1 performed better than both groups at a statistically significant level. Interestingly, in a few cases the raters had mistakenly identified suspected WBMT use and allowed a few compositions with WBMT to slip through unidentified. These results may indicate that WBMT use may be getting tougher to identify among educators. The researcher concluded that the inclusion of proper WBMT use in the curriculum may be a beneficial way to teach students, who will undoubtedly use WBMT, how to improve their writing in L2.

Research Questions

In order to verify the findings from Larson-Guenette (2013) and White & Heidrich (2013), the researchers of this study sought to answer the following two questions: (1) In what ways do students report using web-based machine translation? and (2) What are learners’ attitudes regarding the use of web-based machine translation? In addition to these 2013 studies, however, it was hypothesized that the way in which a student perceives the use of WBMT may be affected by two principal factors: a cycle of dependence in which students use WBMT to such an extent that they must continue to use it in order to maintain their current quality of work output, and the strict imposition of university policies which prohibit the use of WBMT in academic contexts. Thus, in order to investigate the validity of this hypothesis, the researchers intended to answer the following questions: (3) Does the use of online translators promote a perceived increase in use over time? and (4) Do students believe that the use of such services is considered a form of academic dishonesty?

Methods

Participants

Similarly to White & Heidrich (2013) and Larson-Guenette (2013), this study aimed to look into how university policies may affect students’ perception of WBMT and its usefulness in an academic context. In addition to such aims, this study also intended to understand how this same perception may have changed over time supposing that a change in perception may contribute to WBMT being used and regarded as a language learning tool. To ensure that the participants thus had taken introductory Spanish courses at either the high school or the university level, those who were surveyed were all students currently in advanced-level Spanish courses at the University of Tampa, an institution which prohibits the use of WBMT for any work submitted for academic credit. Of the 12 respondents, few indicated that they never used such tools to complete, at least in some capacity, their assignments.

The identities of all the participants have remained anonymous throughout the duration of and following this study so as to encourage truthful responses in spite of the university’s policy regarding WBMT. Given that many of the respondents detailed their use of WBMT, we can thus assume that their responses are truthful because there is no incentive to lie about this behavior.

Materials and Procedures

The researchers used Google Forms as a means of creating the surveys and collecting their data. Both questionnaires were sent out via the university’s email system to students enrolled in advanced-level Spanish courses, and the potential respondents had a two-week period in which they could participate. Before participating in the survey, the respondents had to agree to an informed consent statement which outlined the purpose of the study, the procedures of data collection, the possible risks and benefits of participation, and the confidentiality of the data. After granting their informed consent, the participants had the option to answer a series of questions, some being qualitative in nature and some quantitative. The participants could opt out of responding to any question due to the sensitive nature of the responses they may have had to give. Nevertheless, most respondents did not skip any questions. After completing the survey, each respondent was presented with a debriefing statement, which thanked the respondents for their participation, provided contact information if they had any questions, and instructed them not to share their responses with anyone so as to preserve the impartiality of future responses. After the two-week period, the surveys were closed, and the researchers began their analysis of the data.

Results

With 91.7% of the student participants indicating that they believe WBMT helps them learn new words, it is no surprise that their use of such tools is frequent. Curiously, however, when asked to describe their use of WBMT, the respondents to the student survey indicated to only have used WBMT to either translate individual words (66.7%) or to translate phrases (33.3%). Thus, though frequent, the students’ use of WBMT demonstrates restraint in that they do not translate entire sentences or paragraphs at a time.

Research Questions

The rest of this section will be centered on answering the four originally proposed research questions. Some of these answers are incomplete due to the limitations of this study (see more information in the discussion section).

- Does the use of online translators advanced in Spanish courses promote a perceived increase in use over time?

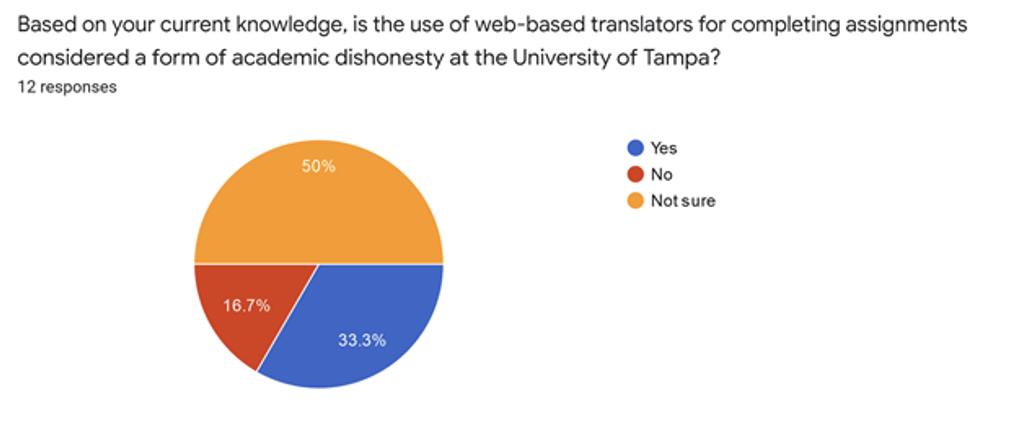

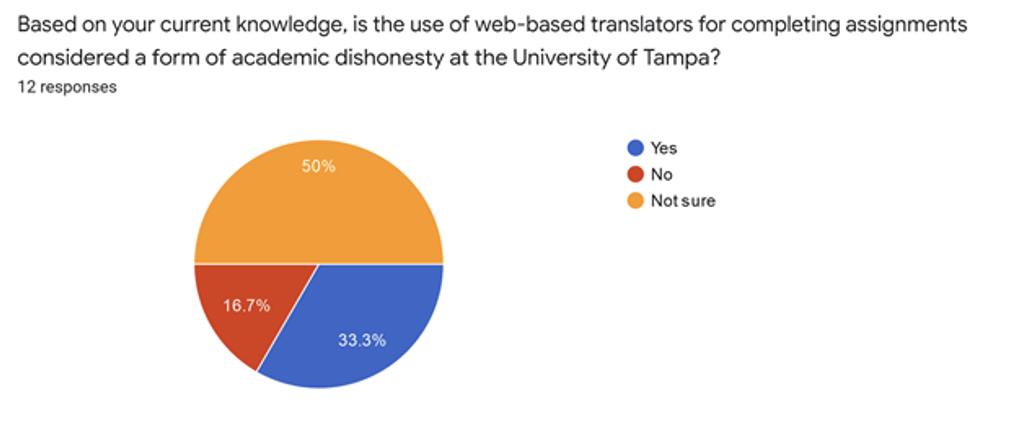

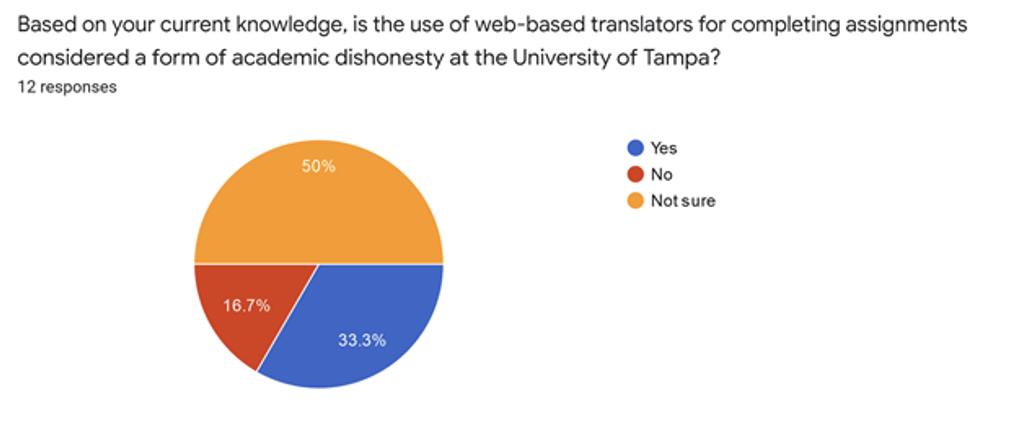

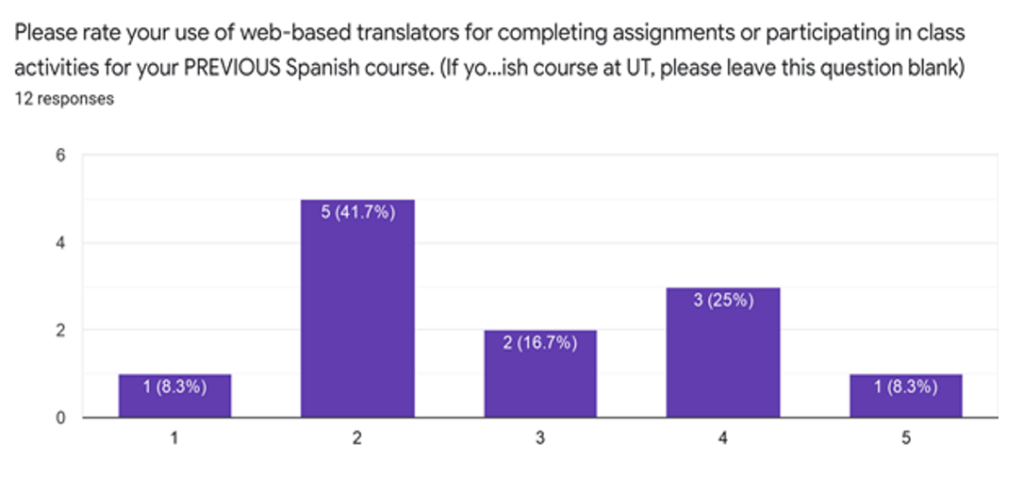

To answer this question, the researchers asked the student participants to rate their use of WBMT in their previous Spanish languages course to their use in their current Spanish course regarding completing assignments for credit. This data was collected on a 5-point Likert scales and is as follows:

Appendix #1

Appendix #2

As we can see, there was not much change in reported use between the previous class and the current class. In fact, 50% of the respondents indicated no change at all, and 33% actually marked a decrease in use, which would suggest that WBMT does not promote a perceived increase in use over time.

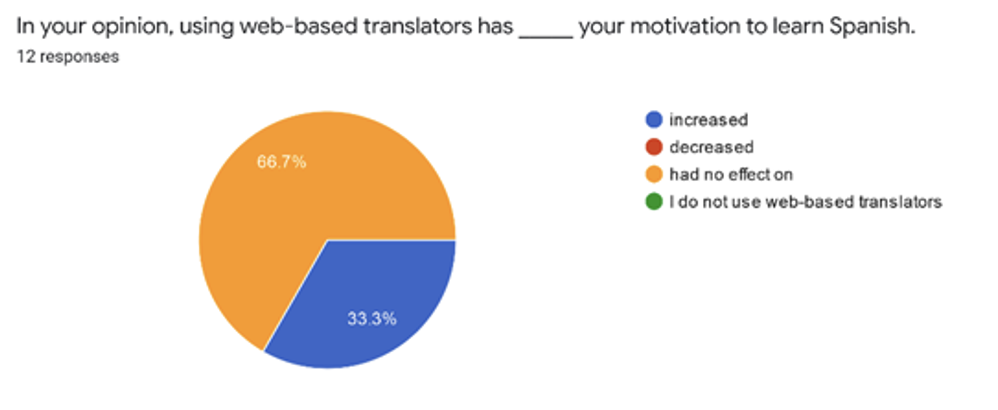

- What are learners’ attitudes regarding the use of web-based machine translation?

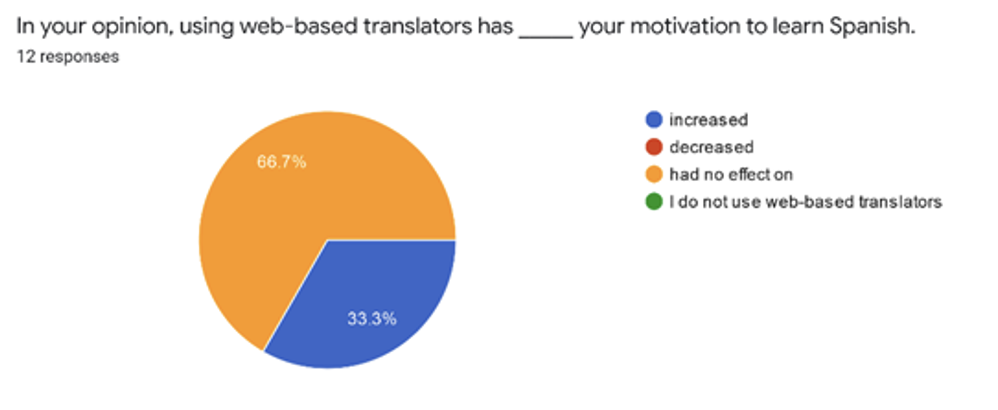

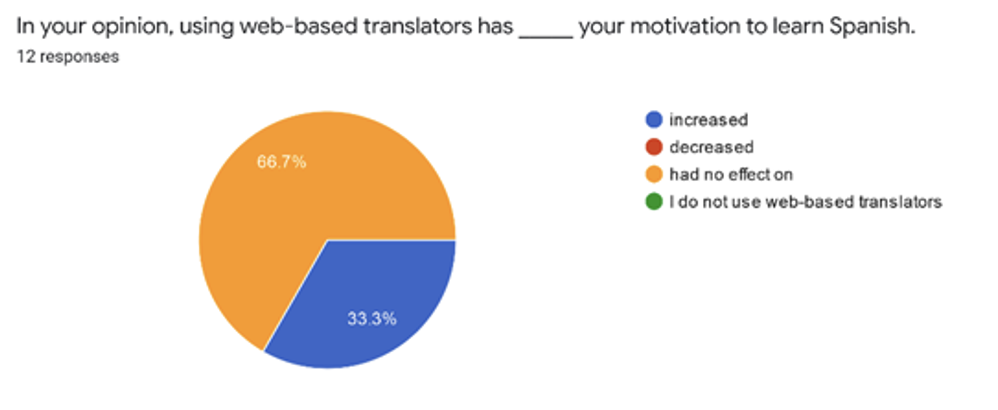

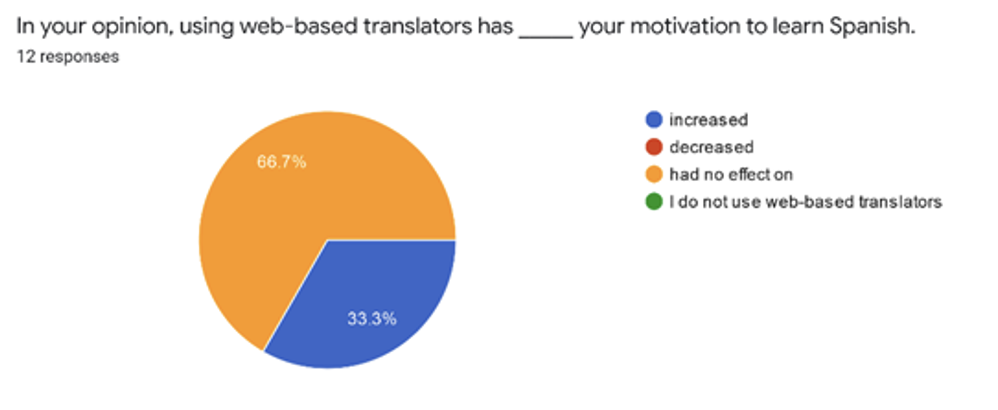

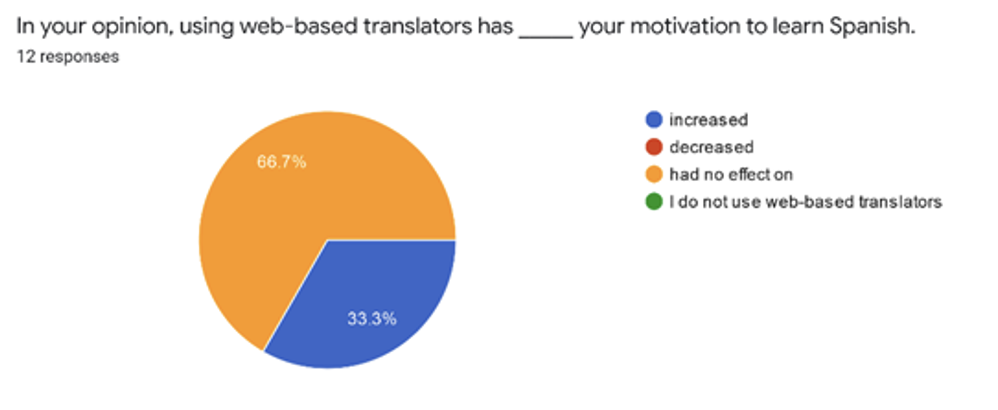

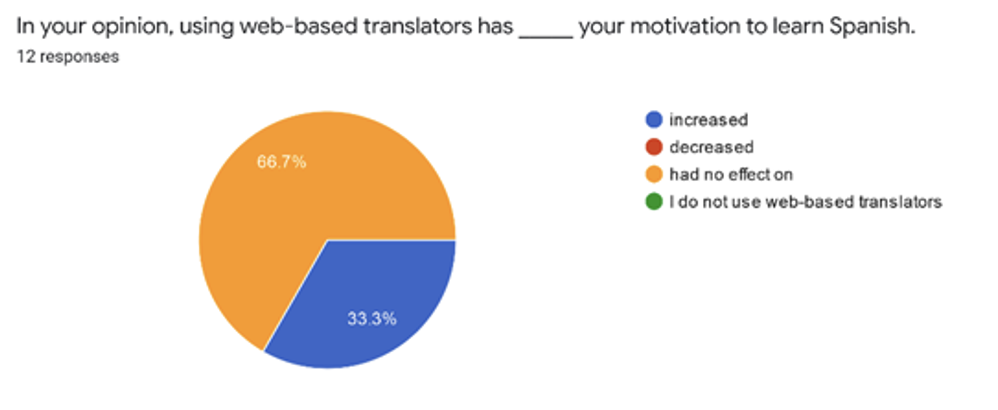

When asked how their use of WBMT may have affected their motivation to learn Spanish, 66.7% of students reported that their motivation has remained unchanged, and 33.3% reported that it improved their motivation.

These findings would suggest that reported learner attitudes regarding the use of WBMT are mostly neutral and tend to be positive rather than negative.

3. In what ways do students report using web-based machine translation?

The answer to this question was found in the qualitative responses that students gave regarding the question “If you believe that the use of web-based translators SHOULD be allowed, please explain your reasoning in a few sentences. If not, please leave this question blank.” Surprisingly, all 12 students provided a response to this question. Based on their responses, 91.7% believe that WBMT had positively affected their abilities in and motivation to learn Spanish, which may indicate that there are effective ways to employ such tools while learning a second language.

9 out of 12 of the responses indicated that students considered that looking up individual words, idiomatic phrases, and discourse markers were legitimate and beneficial uses of WBMT. Many participants also indicated that they look up translations for such linguistic constructions when they notice a gap in their output, which aligns well with the output hypothesis (Swain, 1985) which postulates that SLA takes place when learners become conscious of the gaps in their linguistic knowledge. Thus, if the output hypothesis holds true, the use of WBMT for filling such gaps is a legitimate and productive use of a learner’s time.

25% of the student participants responded that WBMT should only be used in circumstances that do not include any class-related activities. As we saw previously, all 12 student respondents reported that they use WBMT for individual words or phrases, which means that these 3 participants likely agree with the former 9, and they are simply adding a caveat to the use strategy that they all seemed to agree upon. If we consider the university’s policies against the use of WBMT for completing assignments, this strategy seems to be the ideal.

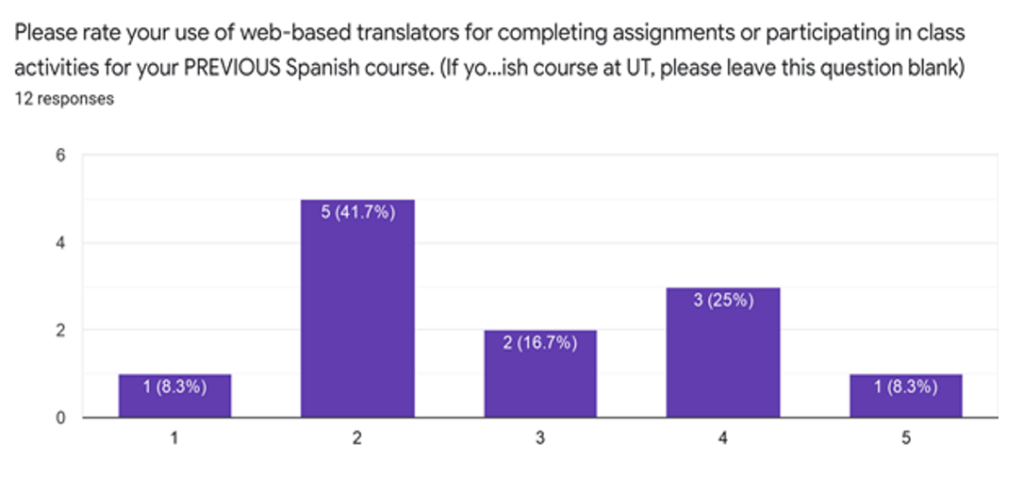

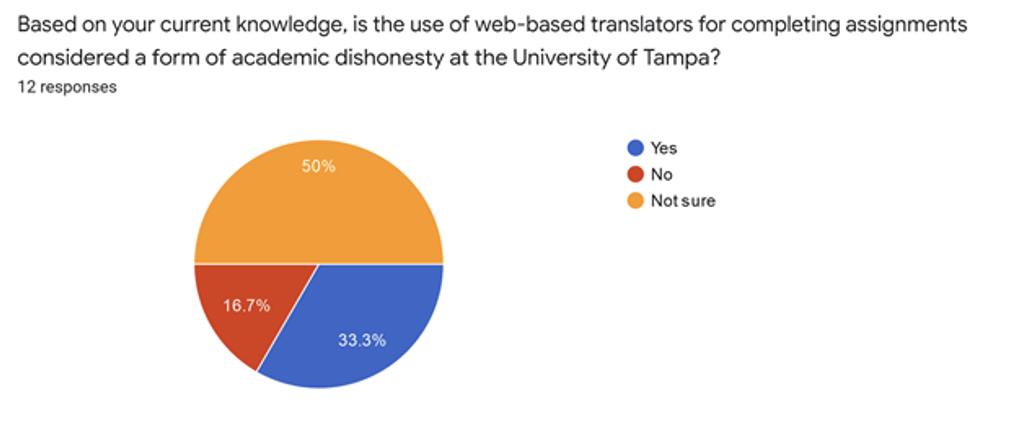

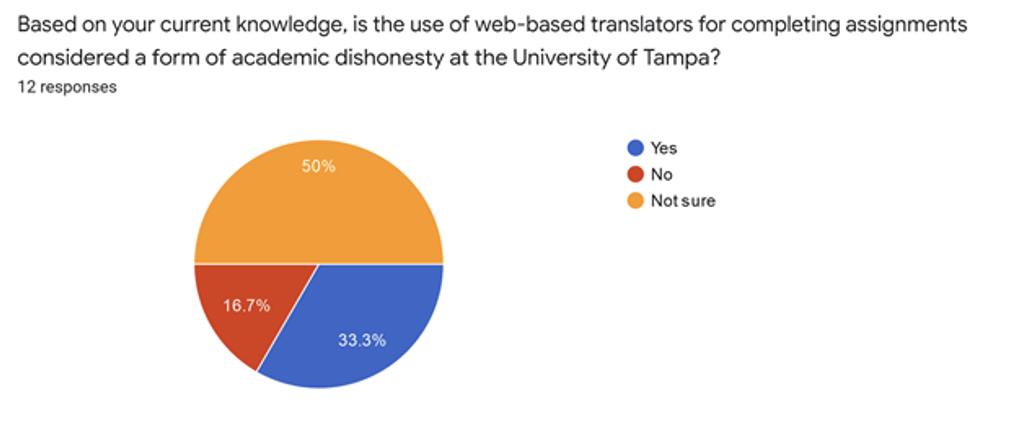

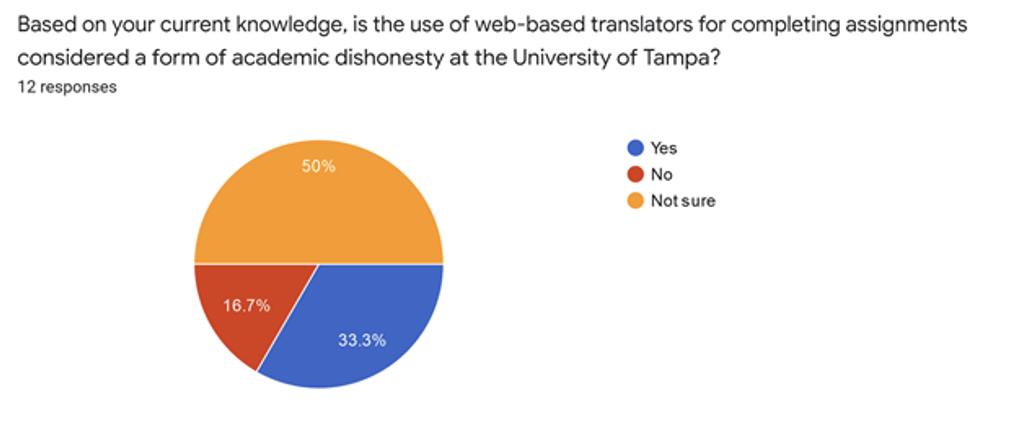

As we can see in Figure 4, 50% of students were not aware that the use of WBMT is considered academic dishonesty at their institution, and an additional 16.7% thought that their use was permitted. These results would imply that, in spite of the warning on each course syllabus in the Spanish program, the majority of the Spanish language students at this institution were not aware of the fact that WBMT is considered a form of academic dishonesty, which may indicate that this policy is not logical from their perspective. To them, their intentions are not to be academically dishonest, but rather, as many students responded, to use WBMT as a tool for filling in the gaps in their output and verifying their already existing knowledge.

Discussion

The results from this study imply that some students use WBMT for completing assignments in spite of the fact that they are aware of the non-use policy. Others report they are not aware of such policy possibly due to not having the intention of being academically dishonest with their use of WBMT. Furthermore, most students report being aware that overuse of WBMT, e.g. translating entire blocks of text written in L1, is generally not effective for their learning and considered academically dishonest. This finding is good news for language instructors who believe that their students do not know how to moderate their use of such services.

Although outright prohibition of the use of WBMT is intended to encourage students to avoid reliance on such tools, prohibiting this tool may be sending the wrong message to students and artificially limiting the scope of their language learning process. Ideally, a Spanish learner at the university level should not just rely on the vocabulary mentioned in class for completing their assignments, but rather they should also be encouraged to engage with the language in any way possible outside of class. When we disallow the use of WBMT for completing assignments, we may be unintentionally fomenting the idea that they are not a helpful resource, when, as this study may indicate, they can be helpful under the correct conditions (assuming that the output hypothesis remains true). Likewise, when students become more familiar with how to effectively use these tools, this may, in turn, reinforce their motivation and language ego because they will be confident in their ability to produce refined output and learn as they do so.

Limitations

This study is generally limited by its sampling. The researchers had to withdraw consideration for the data collected from the instructor survey seeing as only two Spanish language professors responded. Furthermore, the student sample has a selection bias in that the survey was optional and offered no material reward for its completion, so the data is likely skewed toward academically-motivated students who are likely to moderate their use of WBMT compared to non-motivated students. On a Likert scale of 1 (low) to 5 (high) regarding their motivation to learn Spanish, 100% of students marked either a 4 or a 5, which seems to confirm this bias. Another sampling bias that the researchers encountered was that 100% of the student respondents were enrolled in SPA 300, the advanced conversation skills class. This excludes any intermediate students which may have different, and likely less informed, perspectives regarding the use of WBMT. Intermediate students were considered for this study, but unfortunately none of the respondents indicated that they were enrolled in any of the intermediate-level Spanish courses.

Future directions

Due to its aforementioned limitations, if this study were to be reproduced, there should be some material reward for participation so as to reduce selection biases among the student population by encouraging less-motivated students to participate. Furthermore, better outreach and communication, such as allowing the researcher(s) to present on this topic during class, or, at the very least, distributing the survey link multiple times, would facilitate a higher response rate from language professors and students, which would allow for a more complete conclusion regarding how to effectively implement a better university policy regarding the use of WBMT.

Based on the implications gathered from this study in conjunction with those of White & Heidrich (2013), a comparative study should be conducted between similar institutions in order to truly test the effectiveness of the non-use policy regarding WBMT. In such ideal study, one institution would expressly prohibit WBMT as a tool for completing assignments, and the other would allow WBMT to be used for completing assignments accompanied by a methods course which would educate students on how to use WBMT to their benefit. Such comparative study would ideally take place over multiple years, and it would follow individual students’ language learning trajectory from beginning to end, comparing the improvement of their test scores along the way, and conducting interviews regarding their learner affect and motivation.

The original goal of this study was to investigate how the current university policies which prohibit the use of WBMT could be modified to better reflect the tools that are not only widely available to students but to professionals as well. In the professional world, translators and other language professionals use WBMT and other similar tools to learn new words and proper ways of expressing ideas. Thus the researchers of this study propose that these strategies be worked into the general language learning curriculum of undergraduate institutions to reflect a more realistic and modern approach regarding the language learning process and to prepare students for the professional world.

Conclusion

In this study, researchers sought to better understand how students perceive their use of WBMT. Based on the results gathered from the survey, WBMT did not promote a perceived increase in use over time, participants reported WMBT to be a useful tool regarding their individual language acquisition, participants generally reported to use WBMT in a measured and restrained way, and most participants were unaware of the university policy regarding the use of WBMT.

References

Larson-Guenette, Julie (2013). “It’s just reflex now”: German Language Learners’ Use of Online

Resources. Die Unterrichtspraxis / Teaching German, 46(1), 62-74. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/unteteacgerm.46.1.62

O’Neill, Errol Marinus (2012). “The effect of online translators on L2 writing in French”

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. https://www.proquest.com/openview/bea7e311fd45ee30b4833fa235d91d16/1/advanced

Swain, Merrill (1985). Communicative Competence: Some Roles of Comprehensible Input and

Comprehensible Output in its Development. In S. Gass & C. Madden (Eds.), Input in Second

Language Acquisition. Rowley, MA.: Newbury House

White, Kelsey D. & Heidrich, Emily (2013). Our Policies, Their Text: German Language

Students’ Strategies with and Beliefs about Web-Based Machine Translation. Die Unterrichtspraxis / Teaching German, 46(2), 230-250. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/unteteacgerm.46.2.230

Appendix

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4