Dr. Al Delahaye

1929-2021 | Founder of the Department of Mass Communication

Dr. Alfred Newton Delahaye, professor emeritus of journalism and author of two Nicholls histories, founded what is today the Department of Mass Communication.

In fall 1957 he taught the first journalism course ever offered at Nicholls, and in 1973 was instrumental in establishing a degree program called communication arts.

He was born June 4, 1929, near Brusly in West Baton Rouge Parish. At Port Allen High School, he worked as the janitor’s helper. He ranked third academically in the class of 1946 and was cited at graduation for never having missed a day of high school.

In the summer of 1946 he entered LSU as a journalism major. He was a 40-cents-an-hour student worker in the auditor’s office, except for the time spent as a news editor on The Reveille. After his 1949 LSU graduation, he reported for the Franklinton Era-Leader until June 1950 when he began graduate studies in journalism at LSU, working as a graduate assistant. As he neared his August 1951 graduation, he asked his draft board to induct him without delay. About a week later he was in Marine Corps boot camp in San Diego.

Upon reporting to Camp Pendleton at Oceanside, Calif., Delahaye was measured for a snowsuit because he would be in an aggressor platoon. While inquiring about officer candidate school, Delahaye came to the attention of a major who wanted him because of his typing skill. Delahaye then found himself behind a desk in a G-2 office, except when he was undergoing cold-weather and advanced infantry training or involved in “combat exercises.” During a lull at umpire headquarters during a desert exercise near Barstow, Sgt. Delahaye heard the informal comments of legendary Gen. Lewis “Chesty” Puller.

He continued in the G-2 office, even after getting his military occupational specialty changed from “intelligence man” to “combat correspondent.” He did not serve in Korea because the major for whom he worked had to be stateside to look after his wife, who was recovering from tuberculosis, and their three small children.

While on active duty, Delahaye covered a variety show featuring performers from his unit along with Jane Russell and Robert Mitchum; it was a fund-raiser for the Iwo Jima flag-raising monument in Washington, D.C. On weekends Delahaye often visited movie and television studios in or near Hollywood, seeing up close such performers as Red Skelton and Marilyn Monroe. He actually heard Harpo Marx speak at a fund-raiser.

Released from active duty, Delahaye joined the staff of the twice-a-week Houma newspapers of publisher John B. Gordon. He was one of only two full-time news staff members. His partner covered police and sports, and he covered meetings of public bodies and wrote features and editorials, Both took and engraved photos and handled general news. Delahaye also worked as a stringer for United Press.

In 1955 he became the founding president of LSU School of Journalism Alumni.

In 1957 he left Houma for Nicholls. His starting salary was $6,000 a year, and his titles were instructor of journalism and director of publications and public information. Nicholls bought a Crown Graphic camera, and Delahaye turned a White Hall closet into a darkroom, producing pictures for campus and area publications.

In 1959 he was among the first Americans to visit post-World War II Russia. At the opening of the American Exposition, his group, guests of the American Embassy, joined in a toast with Vice President Richard Nixon and Premier Nikita Khrushchev. Delahaye claimed their glasses as souvenirs moments after Nixon and Khrushchev put them down.

At Nicholls, Delahaye soon became the primary founder and coordinator of the Hall of Fame and the Alumni Federation. He started the first regularly published student handbook, The Paddle, and the alumni publication, The Colonel. In 1962 he chose an artist to create a cartoon colonel, which Delahaye popularized as a decal sold by The Nicholls Worth. That figure was popular for 42 years. Years later he designed the university crest and got a professional artist to execute his design.

In 1965 Delahaye began work on a doctorate at the University of Missouri School of Journalism. He spent the next year at Nicholls and then returned to Missouri as the lecturer in the beginning news writing class; during one fall semester, the class numbered 344 students. He supervised reporting labs and during one semester taught a graduate class. He received his Ph.D. in 1970.

“I was teaching ideal students under ideal conditions at Missouri,” he said, “but they would succeed with or without me. So I returned to Nicholls where I thought I could make a difference.”

In 1969 he began about 12 years of just classroom teaching – journalism and English courses, mostly technical writing, When Dr. David Boudreaux allowed him to teach two sophomore journalism classes every semester, a solid foundation for a journalism program was in place. In 1972 he spent the summer in The Netherlands at the Amsterdam Institute for the Science of the Press.

In 1973 Delahaye helped to establish the Faculty Senate and then went on to serves as corresponding secretary for five years.

A 1973 survey of students indicated the viability of a journalism degree program, and so the state board approved one in communication arts. (To have called it journalism would have aroused LSU opposition, Delahaye said.)

The communication arts program gave students a choice of business or creative options. Delahaye taught all the writing and editing courses, Bob Blazier and Ron Simeral the broadcasting courses. Delahaye was the unofficial coordinator of the degree program, which had no budget, no departmental status and no clearly defined faculty until 1990. The first communication arts degree was awarded in 1975.

In 1972 Delahaye became co-editor of the bibliography section of Journalism Quarterly, a responsibility he then held for about 17 years. In 1974 he became the founding president of the Nicholls chapter of the National Honor Society of Phi Kappa Phi. In the early 1980s, Delahaye edited The Temple, the publication of Phi Kappa Theta, national social fraternity.

Throughout his teaching career, he meticulously red-inked major and minor errors sentence by sentence. His thorough exams consisted of discussion and recall questions, and, when appropriate, written and edited matter. He almost never missed or canceled a class or cut one short, attending conventions only in August. He never gave a “bubble-in” test, but his largest writing class at Nicholls never exceeded 44 students.

When Donald J. Ayo became university president in 1983, Delahaye once again became director of publications and public information but continued to teach two advanced journalism courses each fall and spring. He also began a weekly faculty-staff newsletter, Word, for which he did all of the reporting (sports stories excepted) for six and a half years. In 1984 Delahaye was among the first faculty members to receive the title of distinguished service professor.

In 1987 the state board called in out-of-state consultants to evaluate journalism programs across the state. The Nicholls program received more positive statements and fewer negative ones than any other journalism program in Louisiana. The consultants recommended placing faculty and facilities in one building, giving the program a budget and departmental status and setting a goal of national accreditation.

In 1990 Delahaye became a professor emeritus, but continued to teach mass communication courses as an adjunct. He also continued to coordinate mass communication scholarships and awards, which sometimes totaled about $18,000 a year. He worked as a volunteer in his Talbot Hall office every day, even after he stopped teaching. His attitude was “I’ve got to be productive.”

He never said no when someone asked him to edit something. For about five semesters, he taught mass communication courses for nothing, because the university semester after semester refused to pay him the $2,000 he asked. He would say: “I’d rather mow someone’s lawn for nothing than accept payment of $2.50.”

In 1999 and 2005 the Nichols Foundation published two volumes of Nicholls State University history researched and written by Delahaye: “The Elkins-Galliano Years, 1948-1983,” and “The Ayo Years, 1983-2003.” Delahaye planned and coordinated every aspect of the printing, which was paid by the Lorio Foundation of Thibodaux. All sales income, about $30,000, made possible a mass communication scholarship named for Walter M. Lowrey, who was instrumental in hiring Delahaye and getting the first journalism course offered.

In retirement Delahaye, the only Nicholls retiree with an office on campus, enjoyed reading four or five newspapers a day, summer vacations in New York, writing articles and feature stories for university publications and, when asked, red-inking The Nicholls Worth.

Among his most successful former students are Joey Kennedy, a Pulitzer-Prize winner for editorials in 1972; Ken Wells, a Pulitzer-Prize runner-up, writer of fiction and nonfiction books, and a Page One editor of The Wall Street Journal; Tresha Mabile, a television writer and producer, whose work includes five documentaries on Afghanistan and Iraq; and John Gravois, who covered the Bush I and Clinton White Houses for the Houston Post.

Delahaye, who often said he could never be bored in a world of words, people and ideas, was awarded an honorary doctorate by Nicholls in fall 2008. In March 2009, he was honored at a fund-raising banquet attended by about 170 friends, relatives and former students. He was presented with an oak, which today grows in the quadrangle next to a bronze plaque, which honors his more than 52 years of service to Nicholls.

LSU Hall of Fame Induction

Dr. Al Delahaye Obituary

Dr. Alfred Newton Delahaye, Nicholls State University professor emeritus of journalism, died Thursday, Dec. 30, at St. Joseph’s Manor in Thibodaux. He was 92.

Visitation will be on Wednesday, Jan. 5, 2022, at St. Thomas Aquinas on the Nicholls campus from 9:30 a.m. until the Mass of Christian burial at 11 a.m. Internment will follow in St. John the Baptist Catholic Church Cemetery in Brusly between Addis and Port Allen.

He is survived by a niece, Catherine Delahaye Dunn, and a nephew, Don Anthony Delahaye, both of Houston.

He was preceded in death by his parents, Alfred and Lillian Hebert Delahaye, and four brothers: Owen, Tillman, Varney and Leighton.

The family wishes to express special thanks to Ms. Michelle Brickley, Ms. Wilena Cannon, Ms. Constance Cassie, Ms. Ja-Nia Cassie and Ms. Sandra Hutchinson for their care and concern.

He was born in Brusly on June 4, 1929, and was a 1946 graduate of Port Allen High School.

In 1949 he completed a degree in journalism at LSU and then reported for the Franklinton Era-Leader. In the 1950s he completed a master’s degree at LSU, served in the U.S. Marine Corps and was managing editor of The Houma Courier.

In 1957, Delahaye began his career at Nicholls State University where he served as instructor of journalism and director of publications and public information.

During that decade he was also the founding president of the LSU Journalism Alumni Association and founder of the Nicholls Alumni Federation and the Nicholls Hall of Fame.

In the 1960s, he taught journalism for two years at the University of Missouri while in his doctoral program. He received his doctorate in 1970.

In 1972 he began a 17-year stint as co-editor of the bibliography section of Journalism Quarterly.

In the 1970s, he was the founding president of the Nicholls chapter of the national Honor Society of Phi Kappa Phi, served five years as a Faculty Senate officer and established what is today the nationally accredited Department of Mass Communication at Nicholls.

In the 1980s he was recognized as a distinguished service professor. In the 1990s he was recognized as a professor emeritus. Delahaye also authored two volumes of Nicholls history published in 1999 and 2003.

In 2009, he was honored for 52 years of service as a Nicholls professor, administrator and volunteer – and given an oak sapling, which now grows in the university's quadrangle next to a bronze plaque.

In September 2016 he was inducted into the LSU Manship School of Mass Communication Hall of Fame.

Memorial donations may be made to the NSU Foundation, P.O. Box 2074, Thibodaux, LA 70310 for the Al Delahaye Journalism Fund.

Thibodaux Funeral Home is in charge of arrangements.

Dr. Al Delahaye Eulogy

Dr. Alfred Delahaye’s Eulogy Jan. 5, 2021

Delivered by Dr. James Stewart

As an undergraduate I once interviewed a senior Nicholls administrator for a feature who in his office had a framed copy of Sir Isaac Newton’s quote, “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.”

That quote’s presence struck me even in the moment; over time it’s come to have greater resonance.

Nicholls is a young institution. Yet, its sons and daughters have already amassed a truly impressive record. I’ve come to realize these accomplishments were made possible because Nicholls was blessed to be the land of giants. Home to educators for whom teaching was more vocation than occupation – people like Bonnie Bourg, Marie Fletcher, Margaret Jolly, Max Quertermous, Burt Wilson.

Among these Titans, none had greater stature than Dr. Alfred N. Delahaye.

If most who knew him were asked to say the first word that sprang to mind when thinking of Dr. Delahaye, that word might well be “dignified.”

He was meticulous and gracious. He always seemed to know the correct thing to do.

Years after having formally retired, he would show up to the office each day in a coat and tie. In the summer he might relax a little, scaling back to dress shirt and slacks. It was hard to imagine him ever owning a pair of sneakers, shorts or jeans. After all, neighbors claimed he cut his grass wearing an old pair of dress shoes.

Yet there were many surprising facets to discover as you got to know this very private man.

As a student I was floored when I learned he was a Marine. The image of him as a recruit in San Diego with shorn head, screaming a fierce battle cry during bayonet practice seemed so far removed from the refined gentleman who drilled us on AP style rules and loved opera.

But to be fair, he was hardly the typical Marine. He entered the Corps having already earned his master’s degree in journalism. He was one the few leathernecks who might be found strolling across base with a copy of Editor and Publisher rolled up in his pocket – though he would run into others – like his friend Bill Cong – who shared his passion for journalism.

The military way of doing things he found bemusing. He saw little point in marching a pre-set path while on sentry duty and couldn’t understand why a sergeant once told him to abscond with an unattended crate of nails and bring it back to the office where there was no immediate need for the items.

When the Marines found out he was a better typist than marksman, they assigned him duties in a G-2 – or intelligence – office and eventually gave him the designation of “combat correspondent.” In that post, he was able to hone his reporting craft and had the opportunity meet celebrities like Jane Russell and Robert Mitchum (Delahaye wasn’t a fan of Mitchum, describing the actor as a “Boor”).

He often said he learned valuable lessons, in the Corps, and he was proud of his service. Given that he was pretty cagey about his own birthday, in lieu of a cake for him, the department developed the tradition of celebrating each year the Marine Corps’ birthday on Nov. 10th. At these events he liked to point out that the Marines were founded before the nation … and that we should have been using a sword rather than pica pole to cut the cake. They use a sword in the Corps.

He was adventurous. At the height of the Cold War, he struck out with friends for Moscow. As guests of the American Embassy for the 1959 opening of the American National Exposition, they were onsite for the Kitchen Debate between Vice President Richard Nixon and Soviet First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev.

As the crowd dispersed, the proper Dr. Delahaye took the opportunity – drawing no doubt on his Marine Corps experience with the nails – to boost two of the glasses Nixon and Khrushchev had used for a toast. He held onto the glasses for years.

He was deeply devoted to his family. When illness forced his brother Leighton into a Thibodaux nursing home, Dr. Delahaye gave up his regular pilgrimages to New York to see Broadway shows so that he would always be available should his brother need him.

His niece Catherine was a constant source of pride for him. He would often speak of her work tutoring students on their path to U.S. citizenship; how her resilience helped her rebuild her home more than once following the-all-too frequent floods in her Houston neighborhood; how her fortitude led her to take a leadership role with the neighborhood co-op so that she could tackle the root cause of the flooding.

When LSU in 2016 inducted him into its Hall of Fame, and unable to attend the event himself, he asked his niece to represent him. And he knew that when he reached this closing stage of his life Catherine had the strength and grace to help him through it. As usual, Dr. Delahaye was right.

He was a man of strong faith. There was mass each weekend. For him the duties of godfather were an obligation to be approached with extreme seriousness. Fridays during Lent were spent at the St. Joseph’s mass and gumbo. As his formal duties at Nicholls decreased, he began to attend mass the remaining weekdays during Lent at St. Thomas Aquinas Center.

At his core he was a teacher, one who lead by example.

His work as a journalist did not end when he joined the Nicholls faculty.

A master storyteller and keen observer, he continued reporting, spending hours tracking down facts and quotes until very recently.

For example, in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, Dr. Delahaye helped create a newspaper for the evacuees who were living on campus.

In 2015 when a former student was set to argue a case before the U.S. Supreme Court, he contacted The Courier and volunteered to write the story himself.

As a journalist he taught that precision was everything. When he discovered that a computer error at the printing plant had created mistakes in the index of one of his volumes of Nicholls history, he set out with pen and correction fluid to rectify the resulting inaccuracies by hand.

He was a mentor, always teaching. Always guiding … sometimes even when the guidance was unsolicited.

A Nicholls Worth editor would often get through campus mail a marked up copy of the most recent edition. Woe betides the editor who made an exceedingly egregious blunder and received the dreaded notation of “Horrors” with at least one exclamation point.

Not even area professionals were immune to his critiques. In fact, you didn’t even have to be one of his students. A local editor not long ago recounted with a chuckle that he got more than one phone call from Dr. Delahaye with a well-intentioned and on-point observation.

How lucky are we that he chose to teach here. When Dr. Delahaye received his Ph.D. from the University of Missouri in 1970, it was arguably the nation’s premier journalism program. He had the golden ticket. He could have gone anywhere he wished. He chose to return to Nicholls.

He said that the choice had been easy. Students at marque programs were the products of privilege. They didn’t need him.

At Nicholls he could make a difference.

Make a difference he did.

His impact echoes across campus, from every action of the Faculty Senate (which he helped form), to the annual induction of members into the Nicholls chapter of Phi Kappa Phi (of which he was the founding president), to his famous (or infamous, depending on who you talk to) 1973 yearbook picture of streakers. He helped shape the very foundation of the institution.

For those who are not aware of the breath of his contributions to Nicholls as a whole, his role in Mass Communication education alone is – well – nothing short of extraordinary.

He started with a few journalism courses taught in the Department of English. When industry and student demand proved to administration there was a need for an actual degree program, Dr. Delahaye scoured the campus commandeering unused typewriters to build a lab.

From these roots he developed a department that by 1994 had received full accreditation by the Accrediting Council on Education in Journalism and Mass Communications. That accreditation has been reaffirmed four times and he took part in the process each time. Only 114 programs in the world have full accreditation.

As a side note, two of his former students now serve on the 23-member Accrediting Council, one of whom is also a past president of the Society of Professional Journalists.

The success of his students in the arena of communication is outstanding. They have been a part of four Pulitzer Prizes and a runner up to a fifth; served in editorial roles on newspapers ranging from the Wall Street Journal to Chicago Tribune; won News Emmys; produced documentaries for platforms like the National Geographic Channel; operated their own TV stations; served as department chairs at Elon University, one of the nation’s top communication schools; and served as public relations professionals at leading profit and nonprofit organizations. The voice of LSU football and basketball for more than 32 years has been a Delahaye protégé.

The achievement of his students reaches far beyond communication.

I can’t tell you how many people from medical or business professions have told me they took at least one course with Dr. Delahaye and how much it meant to their careers.

The current Chief Justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court signed up for an independent study with Dr. Delahaye. The jurist said he never worked harder in any course even though it was not required for graduation and earned him no academic credit.

Oh, and that former student who argued the case before the U.S. Supreme Court, he won.

To put all of this into perspective, since is first in 1975, Nicholls has had fewer than 1,000 MACO graduates. Some schools produce 600 to 900 a year.

He was driven by a deep dedication to his students and their potential.

And it wasn’t just the students who seem pre-determined for greatness that he cared for. I’m a prime example. After briefly meeting me for the first time during the harried, nightmare that was arena registration, he tracked me down in the ROTC building a few days later.

When I saw him enter the front door, I was certain I was doomed. In my experience, important people came after you only when you were in trouble.

But he was there to hand-deliver an application for a scholarship, one that would allow me to concentrate on my studies rather than seek a parttime-job during the semester.

I wasn’t a likely candidate. I wasn’t even sure I was going to make it through the first semester before getting chased off.

From that point forward he shepherded my career at every step, from writing letters of recommendation for promotion or award, to loaning me a computer and printer while I completed my residency. My most prized possession is the cap and gown he passed down to me with both of our names embroidered inside.

He never forgot a student. If you mentioned one, he could recall where the student sat in class and had some anecdote to relate. He kept files on former students with news releases, marriage and birth announcements and letters for years after he retired.

I could go on for hours, but there is no need. Each of you here knows how much he meant to all of those with whom he came into contact.

In the old newspaper days we would put the number 30 at the end of our stories to indicate their conclusion.

At this point you may think that I would close with that number. But Dr. Delahaye instilled in his students a profound respect for both fairness and an accuracy.

Thirty would be inappropriate.

Always thinking of others, years ago Dr. Delahaye began making plans for this moment so that his family and friends would not be unduly inconvenienced. He wrote a draft of his own obituary and picked out a picture to accompany it, asking me only to ensure that the story was sufficiently proofed when the final details were added.

He then asked if I would deliver this address. I told him that I would be honored to do so.

He thanked me, then said that he had put together some notes for me on that as well.

I said, “No way. That’s where I draw the line. You cannot ghostwrite your own eulogy.”

Caught out, he responded with the sly grin we all know. Then he gave the notes anyway.

There is one thing that I will crib from that document, an Emily Dickinson quote. Going through some of his old files, I found several copies of the quote in various forms. So, it must have had special meaning for him, and it is appropriate for this occasion.

“This world is not conclusion … a sequel stands beyond . . . invisible . . . as music . . . but positive as sound.”

So, Dr. Delahaye goes on to his next assignment.

As for we who remain, his legacy will continue far into the future, guiding us and those who follow us, each generation paying tribute to him by passing along his lessons.

Like his oak that grows in the quadrangle, continuing to provide comfort and beauty to those who travel across campus, we will take our love for him down our continuing paths.

So, I think the more fitting closing should be the Marine Corps moto:

Semper Fi.

A Life of Service

An Oral History

CONTACT INFORMATION

Department of Mass Communication (MACO)

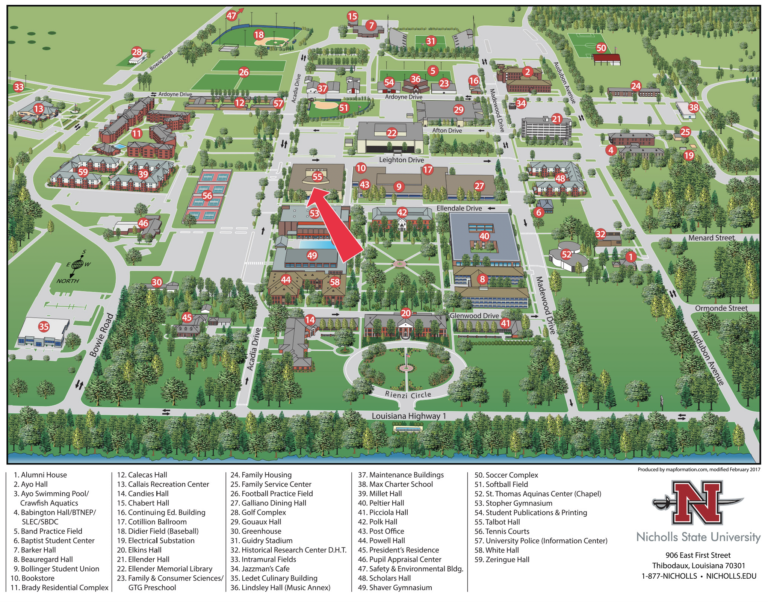

Office Location

102 Talbot Hall

Mailing Address

PO Box 2031, Thibodaux, LA 70310

Phone

985.448.4586

fax: 985.448.4577

Dr. James Stewart, Head

CAMPUS LOCATION